How Omalaytsha navigate tax evasion at Zimbabwe’s borders

Thembelihle Mhlanga

In the shadow of Zimbabwe’s economic turmoil, a vibrant yet clandestine economy thrives along the Beitbridge and Ramakgwebana borders. Here, Omalaytsha—informal cross-border transporters—facilitate the movement of goods, circumventing formal regulations and tax obligations. This article explores the operations of these transporters and their significant impact on Zimbabwe’s economy, revealing a complex web of interactions that highlight the challenges of regulation and the socio-economic factors driving individuals into this informal trade.

The Omalaytsha Experience

Mthabsi Ndlovu and Nkosikhona Dungane, two Omalaytsha, share insights into their daily operations transporting goods from Johannesburg, South Africa, to various markets in Zimbabwe. “A typical day for us starts before dawn. We load our vehicles with goods—clothing, electronics, and foodstuffs,” explains Nkosikhona. “Crossing the border is usually straightforward, especially if you know how to navigate the system.”

Mthabsi adds, “We always have a little something for the ZIMRA officers. It makes things easier.” Their admission underscores a troubling reality: corruption at the borders facilitates the evasion of taxes that could otherwise bolster the struggling Zimbabwean economy.

The Economic Impact of Informal Trade

Zimbabwe Revenue Authority (ZIMRA) Marketing and Corporate Affairs spokesperson Gladman Njanji notes that the general impact of smuggling and false declarations by some of these transporters includes significant revenue loss for the government. “Circumventing import controls and introducing prohibited and harmful substances creates unfair competition for legitimate businesses, leading to an informal economy with many players unregistered for tax,” states Njanji.

Njanji further highlighted that Omalaytsha also abuse the rebate system by splitting their cargo among those who enjoy it and understating invoices. This practice leads to substantial losses for the country. According to Economic Governance Watch, the country loses an estimated $1 billion annually due to porous borders and widespread tax evasion. The current economic instability, marked by soaring inflation and currency fluctuations, has exacerbated the situation, making the need for reform more urgent than ever.

In his press release, Njanji mentioned he could not disclose certain statistics as they are part of their intelligence.

Despite the challenges of regulating informal trade, organizations like the Cross Border Association are attempting to promote compliance among Omalaytsha. Mduduzi Ndlovu, a member of the association, explains their efforts: “We try to educate our members on the importance of paying taxes. Some understand, but many still evade. The lure of quick profits is hard to resist.”

Mduduzi’s comments reflect a broader issue within Zimbabwe’s informal economy. The lack of trust in governmental institutions and the perception that formalizing operations would lead to more burdensome regulations deter many from complying with tax laws. “It’s a cycle,” he laments. “People are caught between wanting to do the right thing and the reality of survival.”

Navigating Corruption and Compliance

The interactions between Omalaytsha and customs officials highlight a deeply entrenched culture of corruption. While some transporters comply with regulations, others resort to bribery as a means to expedite their operations. “If you don’t have something for the officers, you can expect delays,” Mthabsi reveals. This dynamic creates an environment where evasion becomes the norm, further undermining the government’s ability to collect taxes.

The Need for Reform

As Zimbabwe grapples with the implications of its informal economy, the urgent need for reform becomes increasingly clear. Policymakers must consider strategies that support the formalization of informal transporters while addressing the underlying socio-economic issues that drive individuals to evade taxes. This could include simplifying tax processes, enhancing border management, and providing incentives for compliance.

The complexities of the situation are further illustrated by mixed sentiments from local stakeholders. While Omalaytsha like Mthabsi and Nkosikhona provide vital services that keep the economy moving, their operations also perpetuate a cycle of informality that hinders broader economic growth.

The intricate dance between Omalaytsha, local business owners, and customs officials encapsulates the challenges facing Zimbabwe’s economy. As informal trade flourishes in the face of economic hardship, the government must confront the realities of tax evasion and corruption at the borders. By reforming policies and fostering a culture of compliance, there is hope for a more stable economic future—one where both the government and its citizens can thrive.

The story of Omalaytsha is not just one of survival; it is a reflection of the broader economic struggles faced by many Zimbabweans today. Understanding their operations is crucial for developing effective solutions that can help bridge the gap between formality and informality in the nation’s economy.

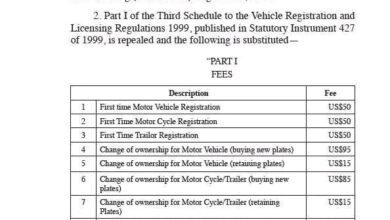

Zimbabwe introduced the SI 7 of 2025, which outlines 19 designated goods, including alcoholic beverages, cement, clothing, and tyres, that are subject to this presumption. Individuals possessing these goods without proper documentation are considered to have smuggled them and are liable for duty payment and penalties.