Displacement and Resilience: The Unyielding Spirit of Lubimbi’s baTonga

Thembelihle Mhlanga

BINGA — A people without history are like trees without roots.” For the baTonga of Lubimbi, this truth cuts deep. Uprooted time and again, theirs is a story shaped by forced displacement but carried forward by unwavering resilience.

From the colonial era to the post-independence period, the baTonga have endured repeated relocations, each one severing connections to ancestral land, cultural identity, and traditional livelihoods.

In 1945, while the world celebrated the end of World War II, the baTonga were dealt a blow that would begin a long chain of dislocation. That year, they were moved from Madilo to make way for the Cold Storage Commission project. Local historian Mr. Tinashe Moyo describes this as the first ripple in a tidal wave of loss. “Our people were moved from Madilo in 1945… it was the start of becoming like ships without anchors,” he said.

Further disruptions came with the construction of the Kariba Dam in the 1950s, a massive hydroelectric project that displaced more than 57,000 people, the majority of them from the Tonga community. This upheaval was followed by the establishment of Hwange National Park, further pushing the baTonga out of their lands in the name of development and conservation. What was taken was more than just territory — it was a way of life, a spiritual bond with land and memory.

Today, the baTonga of Lubimbi ward remain over 220 kilometres from their district centre, making access to healthcare, education, and economic infrastructure difficult. The dislocation has turned their lives into a nomadic existence, where belonging is a dream and survival is a daily challenge. They have lost not only the physical space of their ancestors, but also vital threads of their culture and identity. Elders fear that with every passing generation, these intangible assets are vanishing.

Andrew Muleya, a nonagenarian, recalls a time when his people lived in harmony with nature and upheld strong cultural values. “We used to live in harmony with nature; our traditions and customs were strong. But with each displacement, we lost a part of ourselves.” Octogenarian Sarah Mwinde echoes his sentiment. “Our children are growing up without knowing their roots. It’s like they’re losing their identity.”

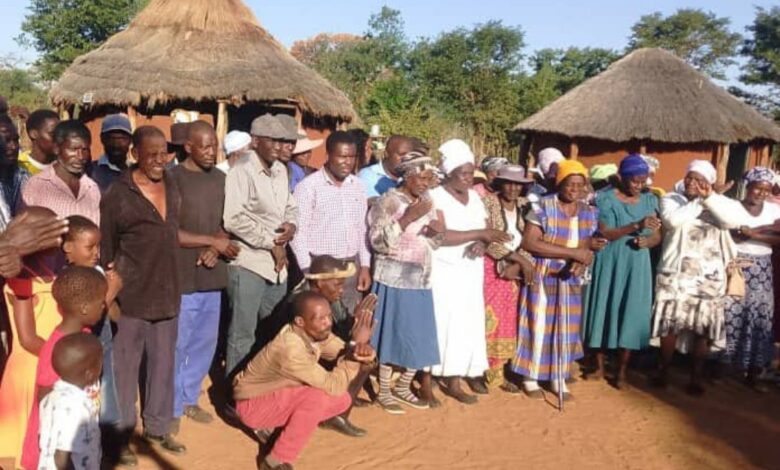

Yet, despite decades of marginalisation, the spirit of the baTonga remains unbroken. Their resilience is visible in every cultural ceremony preserved, in the oral histories passed down, and in the community-led efforts to reclaim what was lost. But their survival cannot rely on resilience alone. It calls for deliberate, inclusive, and just interventions.

Support for the baTonga must begin with the full recognition of their rights to ancestral lands and cultural heritage. There is a pressing need to prioritise community-led development initiatives that reflect their values and aspirations. True inclusion demands their active representation in decision-making processes that affect their lives and futures. Cultural preservation is also critical — language, customs, and traditions must be safeguarded and revitalised, not only for the baTonga’s dignity but for Zimbabwe’s collective heritage. At the same time, economic empowerment and access to sustainable livelihoods must be guaranteed if the cycle of vulnerability is to be broken.

Rewriting the narrative of Lubimbi’s baTonga means acknowledging the historical injustices they have endured and charting a new path built on dignity, justice, and belonging. It requires rejecting top-down impositions of colonial-era thinking and instead embracing development that centres their voice, memory, and vision. Their past is marked by loss — but their future does not have to be.